Uncertainty and the Art of Product Management

Intro

I have previously written about why I made the decision to become a product manager. Now after more than a year in the role, I still find it difficult at times to explain what product management is to someone who has never been a PM. If you were to ask the internet what product management is, you might get something like the below.

I think a more succinct definition that captures the essence of product management is a product manager is responsible for helping an organization to make good business decisions amidst uncertainty. First, lets assume that the goal of every commercial enterprise is to sell a set of goods or services, aka “products”, so as to maximize profitability and ensure future growth. Second, let’s also say that all three of these domains – products, profitability, and future growth – are interconnected and interdependent. You cannot make good decisions about products without considering profitability and future growth and vice versa. Uncertainty refers to the fact that these “business decisions” are never made with perfect information. Therefore the essence of a being a product manager is being responsible for helping an organization to make good business decisions amidst uncertainty.

If you’re reading this and thinking “what the hell does that mean?” or “what a dumb job description!?!?”, I’ve written some reflections on product management below. I hope you find them useful if you yourself are considering a career in product management or if you are one of my close friends or family whom I’ve subjected to mumbled, incoherent explanations of product management in the past.

The “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now”

This section comes primarily from a friend and mentor, Parilee Wang. Before ever becoming a PM, Parilee told me that the primary responsibilities of a a product manager are owning the “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now”. The “What” is short for “What is the customer problem that the business is trying to solve?”. The “Why” is short for “Why is this problem something the business should solve?”. Finally, the “Why Now” is short for “Why should the business solve this problem NOW as opposed to focusing on something else?”. Together these three questions represent a framework for understanding and prioritizing the customer problems that a business should work towards solving.

What does it mean to own these questions? In my experience, it is more complicated than simply having an answer for each. I’ve come to believe that owning the “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now” means that you, as a product manager, are the person responsible for making sure the company, as a collective organization, has an answer to each of these questions. I think a common misconception of product management is that you are responsible for coming up the with answers, but the truth is that you’re actually responsible for helping the business to find them. The difference is subtle but important. More often than not, the answer to any of these three questions can be found within the business and the job of a PM is to ask the right questions and build consensus. In the instances where answers to the questions cannot be easily found within the company, a PM should be helping to lead the search rather than going on a solo mission to determine the answers. Taken together this means somewhat paradoxically that even though a good product manager owns the answers to the “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now”, as a rule of thumb, a product manager should always be asking more questions about the “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now” than he or she is ever answering.

Decisions and Deadlines

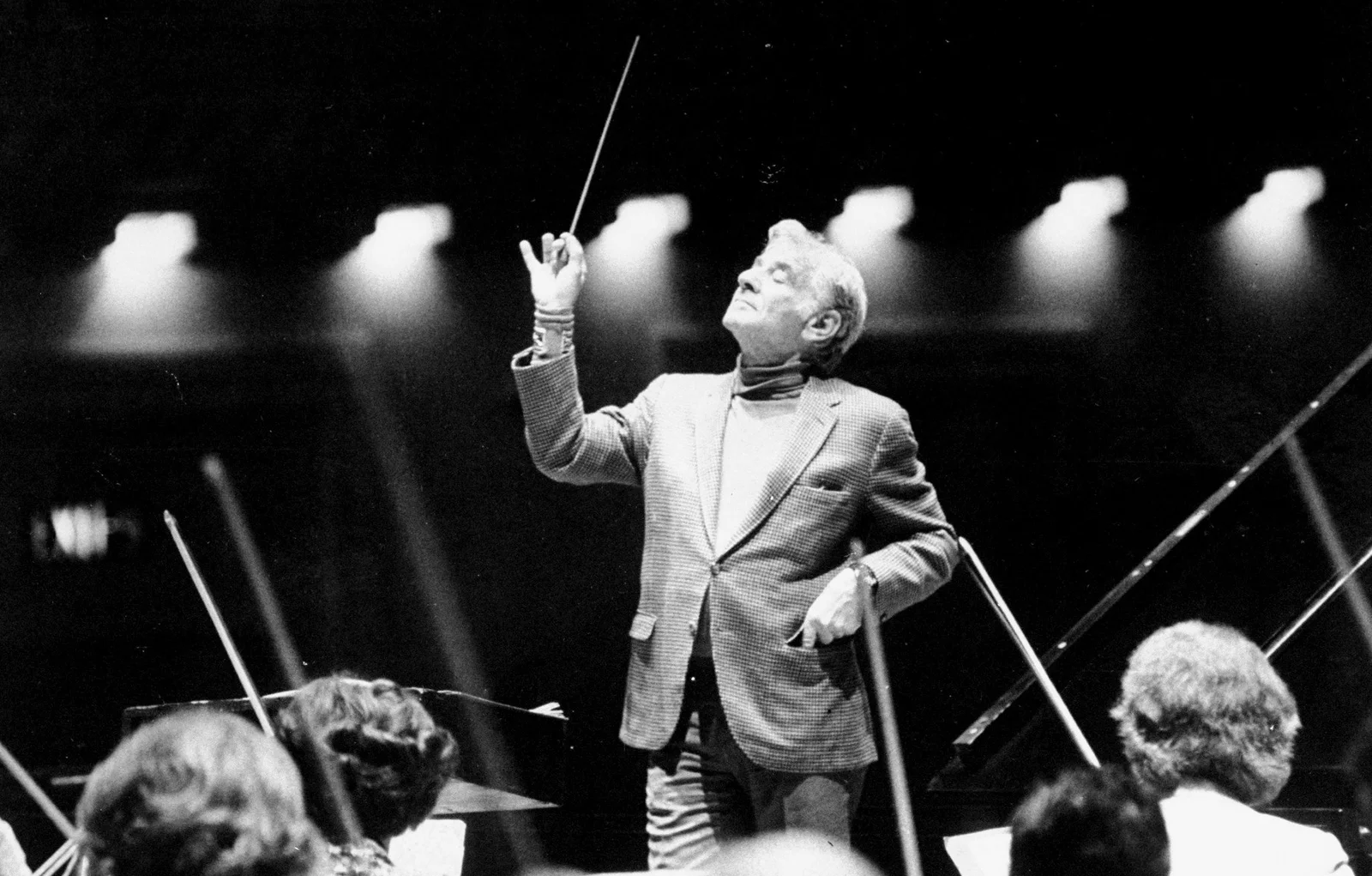

The “What”, the “Why”, and the “Why Now” is a framework for understanding how to prioritize the importance of business problems but the job of a product manager doesn’t end here. PMs are also responsible for execution, i.e. helping to create and bring solutions to customer problems to market. Again, responsible does not mean that PMs are the only owns who make decisions and take action when bringing a product to market. This is probably a generous analogy but I think that this part of the PM job remit is similar to being the conductor of a symphony orchestra. And if you’re wondering, “Why do orchestras need conductors?”, please bear with me.

Does This Guy Matter? Conductor Leonard Bernstein during rehearsal with the Cincinnati Symphony at Carnegie Hall in 1977.

:backhand_index_pointing_up: James Garrett/New York Daily News via Getty Images

Product Managers should not take a hands-on role in bringing a product to market. Similarly, conductors never pick up a violin mid performance. Instead, the best course of action for PMs is to take an incredibly active role conducting (see what I did there) efforts across teams and making sure that all teams are working in harmony (got ya again) to create the best possible solution for the business. But the conductor analogy goes even further than this. I would argue that the most important quality a conductor brings to the orchestra is their initial idea of how to make a piece of music as appealing as possible to an audience. Some people may think that conductors are strict authoritarians, but I believe that the best conductors aren’t beholden to their initial ideas and instead use them as a launch pad to create something unique with the rest of the orchestra during performances and rehearsals.

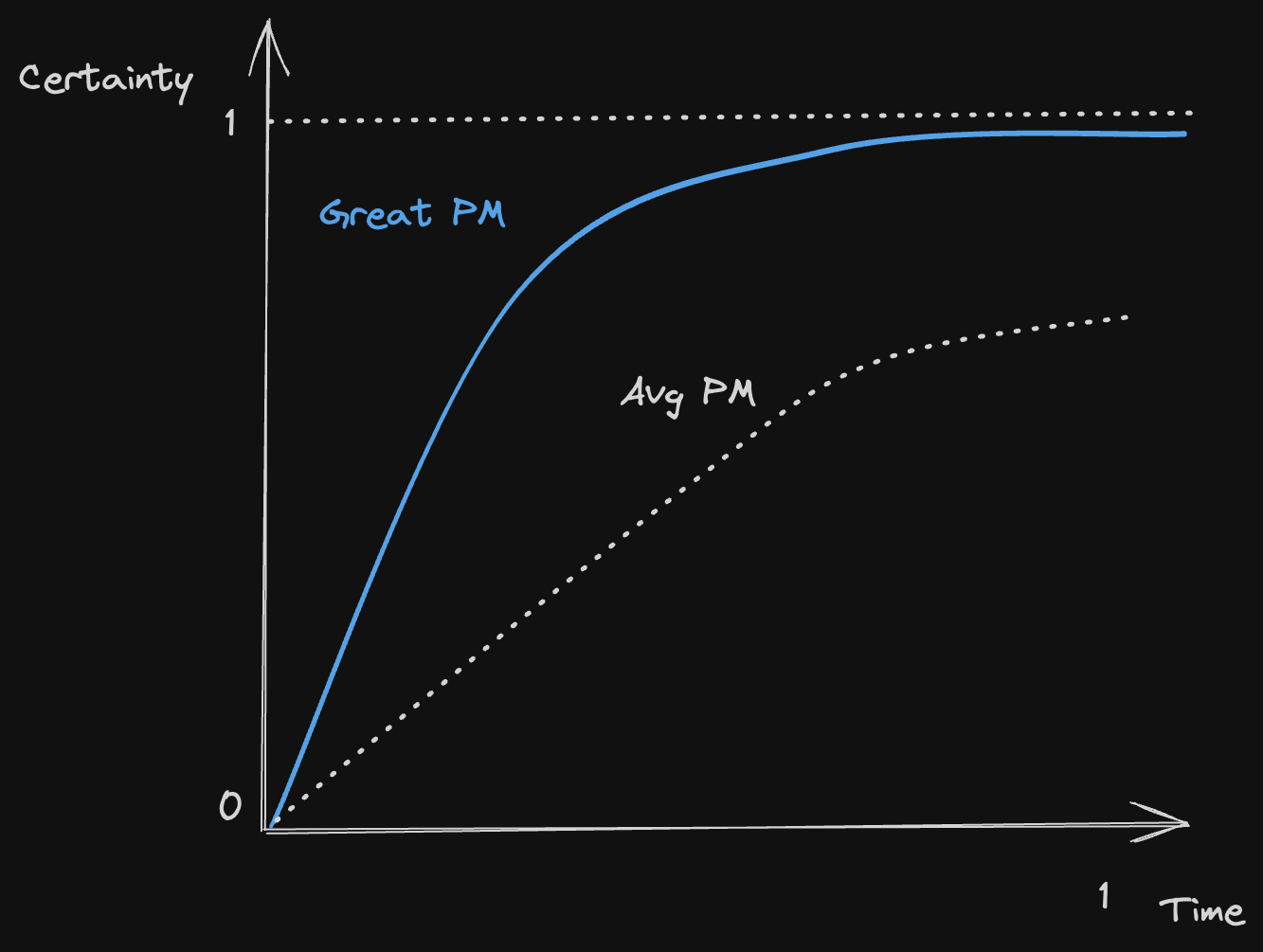

A good product manager must have an idea of what the product solution should sound like (so to speak) but equally important they need to be willing to iterate quickly and ask lots of questions of their own suggested solutions. Complex and difficult business problems are complex and difficult because there are no easy or obvious answers. This is the “uncertainty” that PMs must help a business to navigate. Uncertainty can never be removed completely, but great PMs reduce uncertainty at a much faster rate than your average or simply good PM. The best PMs do this by working quickly to understand a business problem, i.e. identify the “What”, “Why”, and “Why Now”, and then trying to propose a possible solution. The goal of that initial proposal is not to solve the problem then and there but rather to gather feedback from stakeholders as quickly as possible and then iterate again and again until the collective business feels they have reduced uncertainty to a point where development and go-to-market activity can begin with an acceptable risk of miss-investment of company resources.

What about roadmaps and deadlines? A good product roadmap contains product features with well defined “What”, “Why”, and “Why Now”. Additionally, it will contain high-confidence estimates of when these features will be made available to customers. Like every other aspect of product decision making, deadlines are initially made amidst some uncertainty and are normally subject to some change. Deadlines or rather, “estimated delivery dates”, are incredibly important because without them it is impossible to make informed product decisions. Great product teams are good at de-risking the uncertainty around deadlines before communicating them to stakeholders. Product teams that prioritize deadlines above all else do so at the risk of increasing the chance of miss-investment of company resources by reducing the amount of time for the company to iterate on product solutions before finding and investing in the right solution.

Trust is Everything

Trust is the currency of speed.

:backhand_index_pointing_up: Rick Wimer, Vareto engineer, self-described Cloud Cowboy

As I’ve said previously, having the job title of “product manager” means that you are responsible for helping an organization to make good business decisions amidst uncertainty. Said differently, the organization trusts you to help them to make good business decisions. The importance of this trust cannot be understated. When a new PM first joins a company, they inherit a base level of trust from the team who hired them. This base level of trust has been established at least partially by the ability of the Product Team – or in the case of a first PM hire, the leadership team – to demonstrate an ability to make good business decisions over time. If the product team is a great product team, then the base level of trust inherited by the new PM may already be fairly high. Even in the opposite case, the remit of a product manager remains the same but low levels of trust will prohibit a PM from being able to quickly iterate and reduce uncertainty via interactions with internal and external stakeholders. Higher levels of trust between teams encourages open, honest, and quick feedback loops as PMs help organizations to iterate to reduce uncertainty.

A funny thing about trust…Trust isn’t built solely by helping the business achieve good outcomes. I like to think that two or more people choose to trust each other because of mutual interest, mutual respect, and a bit of game theory. Mutual interest, in the case of a PM and stakeholders, is best understood as the success of the company or product. Mutual respect is honoring co-workers equally as both colleagues and also individuals who have interests and lives outside of an immediate work problem. Finally, game theory is a way of saying that PMs and their stakeholders are engaged in a repeated games and trusting one another leads to better shared outcomes than distrust. Great PMs constantly nurture trust because they understand how important it is to their own success and correspondingly the success of the business.