Sleep, TLS, and HTTP Proxies

Background

When I decided to get more serious about running, I bought a running watch. Wirecutter and Amazon reviews convinced me to purchase the COROS Apex Pro and compared to similarly watches, the Apex Pro had two killer features for me:

- It has an incredible battery life

- It tracks different sleep statistics that I was interested in.

COROS, like Garmin and other similar companies, has a smart phone app that is free to use with purchase of a compatible watch. The COROS app is beautifully designed and I love it…BUT… it has a big flaw (for me). I can’t easily bulk export my sleep or other health data that the app has access to.

Not to be stopped from getting what I want, I learned that I can “trick” COROS’s servers to sending me the data I want by proxying and modifying the network traffic being sent from my iPhone to COROS. This post is an exploration into why I wanted my sleep data so badly and some of the things that I learned about proxy servers and internet security.

Why do I care about sleep?

A few months ago, a friend recommended I read Matthew Walker’s “Why We Sleep”.

Prior to reading this book, I had always been someone who prided himself on my ability to function on little to no sleep. In high school, I volunteered as an EMT every Thursday night and that meant I came to school most Fridays without really sleeping. In college, I would frequently pull all nighters before important exams or due dates. I never thought this was a problem. In fact, I was proud of my ability “not sleep”. As an adult, there was less need to be up all night for School or extra curricular activities, but I never prioritized sleep. This book completely shifted my way of thinking!!!

It turns out that habitual lack of sleep is highly correlated with both academic performance and chronic illness, not to mention athletic performance. An MIT study published in Nature, found that Sleep measures accounted for nearly 25% of the variance in academic performance. Studies linking persistent lack of sleep to chronic illness such as cancer have not always been conclusive, however, one large scale study in Europe found the following:

Results: During a mean follow-up period of 7.8 years 841 incident cases of type 2 diabetes, 197 cases of myocardial infarction, 169 incident strokes, and 846 tumor cases were observed. Compared to persons sleeping 7-<8 h/day, participants with sleep duration of <6 h had a significantly increased risk of stroke (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 2.06, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18-3.59), cancer (HR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.09-1.87), and overall chronic diseases (HR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.10-1.55) in multivariable adjusted models. Self-reported daytime sleep at baseline was not associated with incident chronic diseases in the overall study sample. However, there had been an effect modification of daytime sleep by hypertension showing that daytime sleep was inversely related to chronic disease risk among non-hypertensive participants but directly related to chronic diseases among hypertensives.

I had to quickly google Hazard Ratio(s) but it turns out they are simple to interpret. The post from the study above found that people who self reported an average of less than 6 hours of sleep per day were twice as likely to suffer a stroke, ~40% more likely to develop cancer, and ~30% more likely to have any chronic disease compared to participants. This study has been cited by over 200 other academic papers. Stats like this have floored me. Als, we only recently are in a day and age where many people have fitness trackers that they are wearing to bed and tracking sleep. The findings from the Potsdam study relied on self-reported data. In the next couple years, I believe sleep and sleep research will become more influential within Healthcare as the size and quality of data improves.

Why do I care about sleep? It might be the single, greatest contributing factor related to improved mental performance and long term health outcomes and it is mostly within my control.

What does a proxy server look like?

Ok, time for some technical stuff.

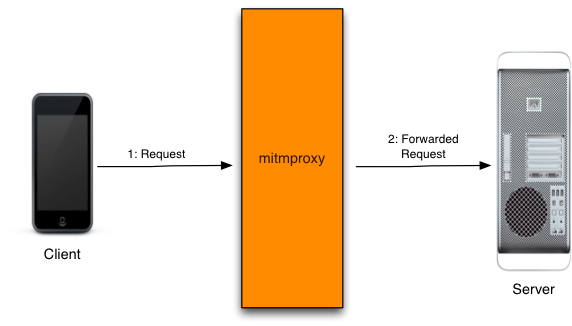

Put simply and according to Wikipedia, a proxy is a server application that sits in between a client requesting resources and a server providing that resource. For my purposes, I want to set up a proxy server that can sit between my iPhone and COROS’s application servers.

Two very good, mostly free proxy applications I found on the web are mitmproxy and Charles Proxy.

The place where most people will first encounter a proxy server is likely at school or at a shared office. A common commercial use case for proxy servers is content control and monitoring. By routing web traffic through a proxy, you can log activity and also limit access to certain ip addresses. Another common use case for proxies might be to bypass censorship or filters. While this sounds similar to a VPN there are slight differences. My favorite use case for HTTP proxy servers is eavesdropping. By having access to the proxy server in between the client and host server, you can “listen in” on the network traffic flowing between the two. Prior to the advent of HTTPS (more below), internet traffic between clients and host servers was not always secure and encrypted and if your traffic was being routed through a proxy, someone with access to that proxy server could see all of the data being sent back and forth in plain text. Now that almost all internet traffic is secured via TLS protocols, a proxy server needs to provide a “trusted certificate” to be able to snoop on network traffic.

What is TLS anyways?

This video helps does a good job going into the nitty gritty.

Here is my admittedly amateur understanding of TLS. TLS is an acronym for Transport Layer Security and that little “s” in “https” means that the website server you are communicating with is using some version of TLS to ensure that the network traffic between your computer and that server is secure. Secure here means that the packets of information being sent back and forth are encrypted and only your browser and the server have the means to decrypt them – assuming you’re not being spied on by a nation state actor with a super computer powerful enough to brute force the encryption.

The “TLS Handshake” is both incredibly common and incredibly important to how the internet works. Literally every website you visit (well almost every) will engage with your browser in a TLS handshake prior to doing anything else. How does it work? Public private key magic! Here is my brief story to help explain how TLS works

First your browser reaches out to the server and says “Hello, I am Dave and I can speak one of seven different encryption languages.”

Next the server responds by saying “Hello Dave! I am xAYSxAyz9 server. Here is my ID card (certificate) to prove I am who I say I am. You said you speak gobble gook. Let’s communicate that way! Here is a password (public key) you can use to securely communicate with me”.

Because metaphorical me or my friends have been burned one too many times by servers pretending to be someone they aren’t, I decide to take a close look at the certificate. I want to make sure a trusted third party, a certificate authority, has put their signature on the certificate so that I know I can trust it. I want to beware of self-signed, i.e. probably fake certificates like the fake IDs kids try to pass by bouncers at bars before they turn 21. This server’s ID looks good!.

Next I tell the server “OK xAYSxAyz9, I trust you are who you say you are. But I want to be extra careful, so let me create a new password (shared secret) that we can use to communicate.” I create the shared secret, then I use the server’s public key and the gobble gook algorithm to encrypt it. “Here you go server. Let’s use this new password (encrypted) to communicate!”

The server takes this new encrypted password and decrypts it using the private key associated with its public key. Now both myself and the server have the same shared key we can use to communicate privately and bingo bango we are off to the races.

What is the difference between HTTP and HTTPS you might ask? HTTPS is “secure” meaning it requires encryption via TLS whereas HTTP does not. Most modern browsers heavily discourage users from interacting with websites that do not have HTTPS.

What does TLS and SSL certificates have to do with proxies anyways? If you want to see the network traffic being sent between your smart phone apps and those app’s servers, you need to get in between the TLS communication happening between your phone and the server. In order to do this, you’ll need to set up an HTTPS proxy server to sit in between your phone and the app server. Your phone needs to trust this HTTPS proxy server and trust here means that your proxy server needs to have access to a valid certificate from a certificate authority. When you put all these things together you’ll have your smart phone communicating securely with your proxy server via TLS and your proxy server communicating securely with the app servers via TLS.

Data and stuff

Time for some data about how good a sleeper I am.

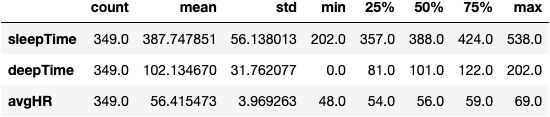

Summary Stats

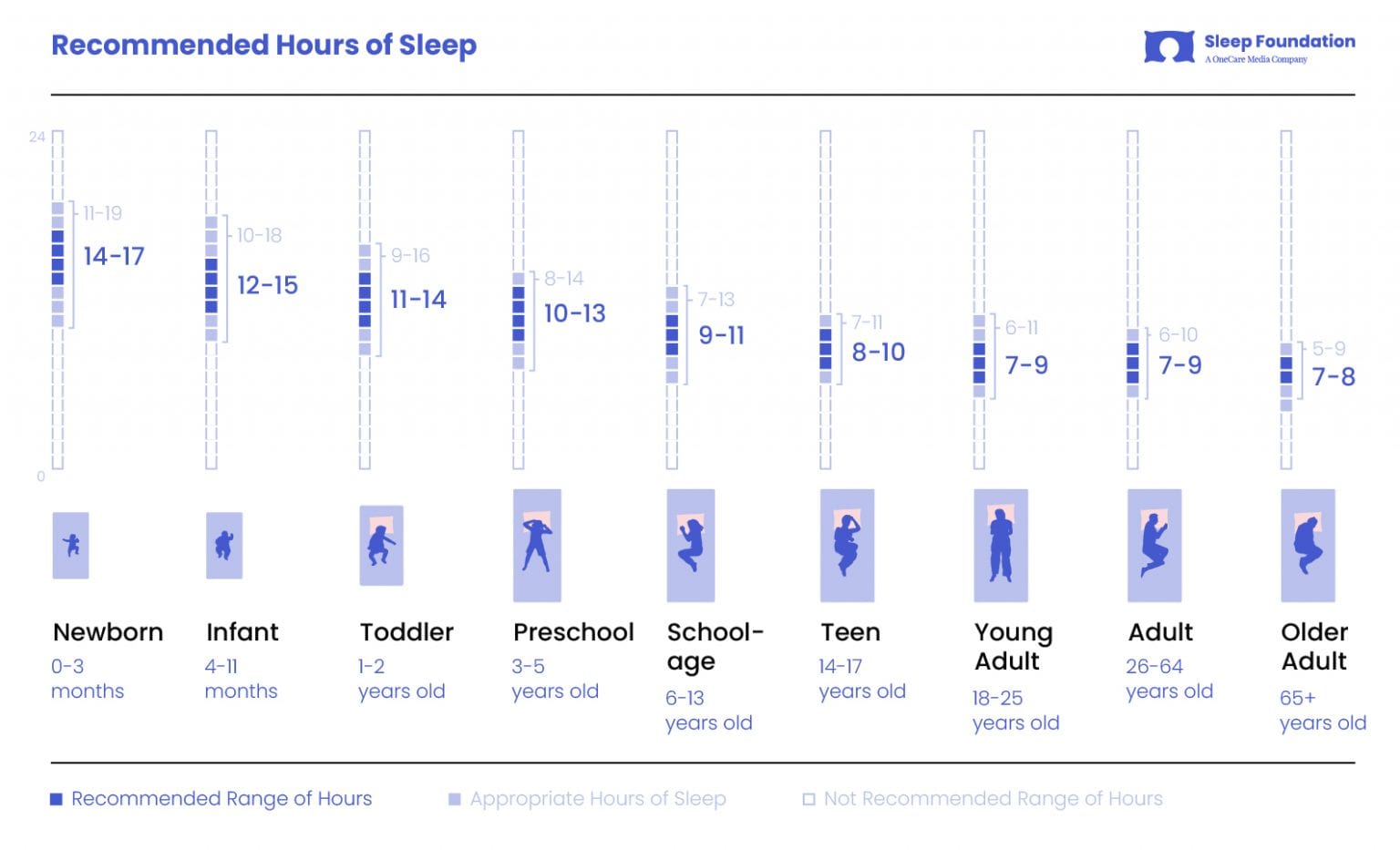

According to the Sleep Foundation, the “Appropriate Hours of Sleep” per night for someone my age is between 6-10 hours and the “Recommended Range of Hours” is between 7-9 hours. My median sleep time of ~6.5 hours is within the acceptable range, but I have room for improvement. I’ll have to ask Emma for some tips given she is a much better sleeper than I am.

Side Note: I discovered that there is a David Rapoport on the Medical Advisory board of the Sleep Foundation. Perhaps, he might be willing to give some tips to someone who shares a very similar name and a budding interest in sleep.

Cool Graphs